Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The role of institutional support in determining the balance between market and strategic coordination in political economies. The analysis suggests that in spheres central to firm endeavor, the extent of market vs. strategic coordination varies across political economies. The document also explores the complementarities between labor relations, corporate governance, inter-firm relations, and policy regimes associated with social protection and product market regulation.

What you will learn

Typology: Study notes

1 / 46

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Peter A. Hall and Daniel W. Gingerich

How do national variations in the institutions of the political economy affect economic performance? This question has been central to comparative political economy for many years. Most answers given to it focus on institutions in a single sphere of the political economy. In economics, there are large but separate literatures on labor and financial markets. One explores the impact of labor regulations, social regimes, and trade unions on growth or unemployment (Nickell 1997; OECD 1994; Calmfors and Driffil 1988). The other considers the effects of accounting standards, the legal standing of owners or creditors, ownership patterns, and equity or bank-based finance on levels of investment or growth (Carlin and Mayer 1999a, 1999b; LaPorta et al. 1998a; Huang and Xu 1998; Mayer 1996). A similar separation is evident in political science. Although neo- corporatism can be defined in broad terms (cf. Katzenstein 1985; Schmitter and Lehmbruch 1978), analyses of its economic impact usually focus on the organization of the trade union movement, considering its interaction mainly with the partisanship of governance (Cameron 1984; Alvarez et al. 1991; Garrett 1999).^1 An entirely different literature examines the structure of financial systems (Verdier 2000; Cox 1986; Zysman 1984). 2 However, there are good reasons to expect interaction effects among institutions across spheres of the political economy. In recent years, significant interaction effects have been found between monetary institutions and those governing wage coordination (Franzese 2002; Cukierman and Lippi 1999; Soskice and Iversen; 2000;Iversen et al. 2000; Iversen 1998; Hall and Franzese 1998). But investigation of such effects among other institutions has barely begun (cf. Fehn and Meier 2000; Caballero and Hamour 1998; Nicoletti et al. 2000). The problem can be described as one of identifying institutional complementarities in the macroeconomy. Economists have identified complementarities among the activities of firms: marketing strategies based on product customization, for instance, can be complementary to computer-controlled machines on the production line (cf. Jaikumar 1986; Milgrom and Roberts 1990; 1995). It is plausible to posit analogous complementarities among the institutions structuring relations in the political economy. One set of institutions is complementary to another when its presence raises the returns available from the other. Here, we refer to the returns to the actors involved in the relevant activities that feed ultimately into national economic performance.^3 The requirement for any investigation of this issue, however, is a theory specifying why two or more institutions might be complementary to each other, and

Association, San Francisco, August 2001. It remains a preliminary draft. Comments welcome. Peter A. Hall, Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 27 Kirkland Street, Cambridge MA 02138; phall@fas.harvard.edu. Daniel W. Gingerich, Department of Government, Harvard University, Littauer Center, Cambridge MA 02138; gingeric@fas.harvard.edu.

where such complementarities are located in the political economy. Aoki (1994) offers important observations about the issue but focuses only on the case of Japan. Much of the literature on comparative capitalism suggests that political economies contain such complementarities, but most contributions to it address a limited number of countries and do not specify the complementarities in readily generalizable terms (Crouch and Streeck 1997; Whitley 1999; Hollingsworth and Boyer 1997; Albert 1993). In this context, a new body of work on ‘varieties of capitalism’ is important (cf. Hall and Soskice 2001b).^4 Its formulations contain a general theory about the nature of the institutional complementarities found in the macroeconomies of the developed world. Applying the new economics of organization to the macroeconomy, this literature develops a distinction between two modes of coordination, one based on competitive markets and the other on strategic interaction, which provides a foundation for understanding many kinds of complementarities. Expressed in the most general terms, the approach suggests that institutions supporting effective strategic (or market) coordination in one sphere of the political economy will usually be complementary to institutions supporting analogous coordination in other spheres. It suggests that nations cluster into identifiable groups based on their reliance on market or strategic modes of coordination. From this follow many important contentions about variations in economic performance, comparative institutional advantage, national responses to globalization, and comparative public policy, which are grounded in a rich set of comparative case- studies (see the references in Hall and Soskice 2001b).^5 However, the core postulates of this approach have not yet been subjected to empirical tests based on aggregate analysis of a large number of cases. As yet, we do not even have a quantifiable measure for the character of coordination, the concept at the heart of the analysis. This poses many problems. Case-studies have been used to classify nations into general categories, but reliance on such broad classifications has meant that a theory designed to offer insights about all the developed nations is sometimes misinterpreted to be one that speaks only to a few ideal types, and the position of many nations within these categories remains ambiguous. The object of this paper is to address these problems, by devising indicators for the central concepts of the varieties of capitalism approach and subjecting its core contentions to aggregate empirical tests. We begin by developing indices to measure the balance between market-oriented and strategic coordination in the political economy. We then assess the core postulates of the theory about institutional complementarities in the macroeconomy, devising further measures for this purpose. Finally, we examine patterns of political adjustment and institutional change in order to assess the durability of the national distinctions identified by this approach. Before considering its specific propositions, we open with an overview of the varieties-of-capitalism perspective. 6

1. The Varieties of Capitalism Approach

In contrast to the large literature focused on national labor movements, varieties-of- capitalism analyses assumes that firms are the central actors in the economy whose behavior aggregates into national economic performance. In order to prosper, firms must engage with others in multiple spheres of the political economy: to raise finance (on financial markets), to regulate wages and working conditions (industrial relations), to

among them, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are also generally identified as liberal market economies. Germany provides a good example of a coordinated market economy. Its firms are closely-connected by dense networks of cross-shareholding and membership in influential employers associations. These networks provide for substantial exchanges of private information, allowing firms to develop reputations that permit them some access to capital on terms that depend more heavily on reputation than share value. Accordingly, managers are less sensitive to current profitability. In the presence of strong trade unions, powerful works councils, and high levels of employment protection, labor markets are less fluid and job tenures longer. In most industries, wage-setting is coordinated by trade unions and employers associations that also supervise collaborative training schemes, providing workers with industry-specific skills and assurances of available positions if they invest in them. Industry associations play a major role in standard-setting with legal endorsement, and substantial amounts of technology transfer take place through inter-firm collaboration. Hemmed in by powerful workforce representatives and business networks, top managers have less scope for unilateral action, and firms typically adhere to more consensual styles of decision-making. It should be apparent that, in order to perform their core functions, firms in coordinated market economies like that of Germany must engage in strategic interaction in multiple spheres, although the institutions on which they rely and the quality of the outcomes may vary from one to another. Austria, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland are usually also identified as coordinated market economies.

2. Establishing Coordination as a Crucial Dimension

In sum, the varieties of capitalism approach posits an underlying continuum, running between market and strategic coordination, which distinguishes among political economies according to the ways in which firms coordinate their core endeavors. Although the quality of coordination is difficult to measure directly, it is based on the type of institutions available to support it. Accordingly, factor analysis provides an appropriate technique for assessing the validity of such propositions. It is designed to identify commonalities that may be unobservable in themselves but that correlate with a range of observable variables (Harman 1976). Varieties of capitalism theory generates three hypotheses that can be tested using such an analysis:

H1 : The character of coordination constitutes a key dimension stretching across spheres of the political economy.

If this is correct, a factor analysis of variables representing the institutional conditions associated with different types of coordination in various spheres of the political economy should identify a principal component loading on the relevant variables across spheres of the political economy. The results will be stronger if the analysis identifies a single such component.

H2 : This dimension reflects variation along a spectrum running from market coordination to strategic coordination.

If this is correct, the underlying factor identified in the analysis should be positively correlated with indicators for institutional support for strategic coordination and negatively correlated with indicators for institutional support for market coordination.

H3 : Because institutional complementarities make it advantageous for nations to develop similar forms of coordination across spheres, it is possible to identify a distinctive set of liberal market economies that make extensive use of market coordination and another set of coordinated market economies that make extensive use of strategic coordination.

If this is correct, when the factor loadings are used to construct scores for each nation, the nations identified by the theory as liberal market economies should be located toward the 'market' end of the dimension, and those identified as coordinated market economies should be located closer to the ‘strategic’ end.

The central obstacle to such an analysis is the paucity of relevant indicators available for more than a few countries. The measurement of coordination poses special difficulties. In principle, types of coordination are observable, but intense observation is required. Only one sphere has been the object of such observation, namely that of wage bargaining. Accordingly, we employ two independent assessments of coordination in wage bargaining. The other variables used in the factor analysis are all indicators of institutional features of the political economy that can reasonably be said to provide support for or to reflect the operation of one type of coordination or the other. We have deliberately identified variables that extend across spheres of the political economy, including ones pertinent to labor relations and corporate governance. The observations were drawn from the 1990-95 period, the latest for which comparable data is available. The variables employed in the factor analysis are as follows:^10

Shareholder Power: reflects the legal protection and likely-influence over firms of ordinary shareholders relative to managers or dominant shareholders. It is a composite measure of legal regulations covering six issues: the availability of proxy voting, deposit requirements for shares, the election of directors, the legal recourse available to minority shareholders, shareholders’ rights to issues of new stock, and the calling of shareholder meetings. Regulations governing each issue are coded 0 or 1 and summed. Higher scores indicate that ordinary shareholders enjoy more rights vis-a-vis managers and dominant shareholders (La Porta et al. 1998a: 1130)

Dispersion of Control : indicates how many firms in the economy are widely-held relative to the number with controlling shareholders. Taking the smallest ten firms with market capitalization of common equity of at least $500 million at the end of 1995 as a sample of firms, it reports the percentage that do not have a controlling shareholder, defined as one who controls, directly or indirectly, more than 10 percent of the voting rights in the firm. Higher values indicate that larger proportions of firms in the economy are widely-held. (LaPorta et al. 1998b: Table II, Panel B)

Size of Stock Market : the market valuation of equities on the stock exchanges of a nation as a percentage of its gross domestic product in 1993. (Oecd.org/corporate affairs)

economy. Table 2 includes the two other indices in the literature most likely to tap this dimension, although Soskice (1990) focuses on wage coordination and both are based on more subjective assessments of the cases (cf. Hicks and Kenworthy 1998). All three indices confirm the plausibility of the distinction between LMEs and CMEs, although there are some differences in the ranking of countries inside each of these groups and of some countries not assigned to them. For this reason, we would be cautious about attributing too much significance to the precise score a nation receives on these scales relative to the nations around it. It is clear that Austria is a highly-coordinated economy but whether Germany, Sweden or Norway is the next most-coordinated is less certain. However, the basic distinction that the varieties-of-capitalism literature draws between strategic and market coordination is affirmed here, and the coordination index should be useful for those seeking a broad measure for the types of coordination prominent in a political economy.

3. Institutional Complementarities in the Macreconomy

As we have noted, one of the most important features of the varieties-of-capitalism perspective is its emphasis on institutional complementarities. The approach sees the political economy as a set of a highly-interdependent arenas, where the impact of a specific set of institutional practices in one sphere—both on the behavior of firms and on economic performance—depends on the character of institutions in other spheres. This literature identifies many such complementarities, each with a specific rationale (Hall and Soskice 2001a). However, the unifying logic behind them derives from the approach's emphasis on the importance of coordination to the success of firms' endeavors. This means that most of the complementarities identified by the theory are ones in which institutions in one sphere of the economy enhance the coordinating capacities of actors in it and in other spheres. These may be capacities for market or strategic coordination. Although more could be cited, we outline the logic behind three of the most important complementarities identified by this theory:

setting will be more efficient, because they enable managers to reduce staffing levels or limit wages more quickly in response to fluctuations in current profitability.

The approach identifies a number of other complementarities in liberal or coordinated market economies that cannot be discussed at length here. Estevez et al (2001) argue that social policies providing generous employment and unemployment protection will be complementary to production strategies based on the use of specific skills because they provide incentives to workers for acquiring those skills (cf. Mares 2000). Casper (2001; Teubner 2001) shows how systems of contract law can be complementary to forms of inter-firm coordination. Hall and Soskice (2001a; Soskice

coordination in labor relations, nations should not be distributed randomly across the dimensional space but should cluster toward its two poles.

Figure 1 provides the relevant evidence, arraying nations on a two-dimensional plot with standardized scores for coordination in corporate governance on the X-axis and standardized scores for coordination in labor relations on the Y-axis. The results are broadly supportive of the hypothesis. As the regression line indicates, there is a strong and statistically-significant relationship in the predicted direction between coordination in labor relations and corporate governance. Nations cluster toward the southwest and northeast quadrants of the diagram, as the theory would lead us to expect. Six nations, all liberal market economies, cluster to the southwest, on or below the regression line. Most other nations cluster toward the northeast. Japan and Switzerland are the two most obvious outliers. We are inclined to view their position as the result of measurement error associated with the limitations of our measure for coordination in corporate governance. The latter attaches considerable weight to the size of the stock market and both nations have large stock markets relative to their GDP. But there is also extensive cross-shareholding in these nations not picked- up by our measure of shareholder dispersion because many of the relevant holdings fall below our 10 percent cut-off (Windolf 1999; Roe 2000). Nevertheless, these cross- shareholdings limit hostile takeovers and serve as vehicles for network monitoring. In short, we think an accurate assignment of these cases would put them into the northeast quadrant of the diagram. The coordination of labor relations in the Netherlands and Belgium may also be underestimated here, reflecting OECD estimates of coordination that may be slightly low. Given the potential for such measurement error, however, the congruence across nations between corporate governance and labor relations is striking. The proximity of various nations to one another in this institutional space is also interesting. Correcting for measurement error, there are four distinct clusters of nations. Among the liberal market economies, the United States and the United Kingdom appear as relatively ‘pure’ cases, while four other liberal market economies stand slightly apart by virtue of systems of corporate governance in which market coordination is not as fully developed. On the other side of the Figure, the nations most often identified as coordinated market economies all lie near or above the regression line, indicating high levels of strategic coordination in both their labor and financial markets. Four nations, Spain, Portugal, France and Italy all lie to the east in the Figure but below the regression line. This is especially interesting because there has been some controversy about whether these nations are coordinated market economies or examples of another distinctive type of capitalism (Hall and Soskice 2001a; Rhodes 1997). Although Figure 1 does not address the semantics, it clarifies some of the issues. These nations all have institutional capacities for strategic coordination in labor relations and corporate governance that are higher than those of LMEs. However, their capacities for strategic coordination in labor relations tend to be lower than those in northern Europe, perhaps because their union movements are still divided along what used to be called ‘confessional’ lines. Although strategic coordination is clearly more important in these nations than in liberal market economies, there may be systematic differences in the operation of southern, as compared to northern, European economies. 14

Broader Types of Complementarities Of course, the complementarities between labor relations and corporate governance are only one set among many posited by the varieties-of-capitalism literature. As such, they constitute a small sample of a broader phenomenon. It is possible that the cross-national congruence we have found in these spheres is simply coincidence rather than an indication that the general approach to complementarities of the varieties-of capitalism perspective is valid. To establish this with more confidence, other sites in which such complementarities are said to exist should be examined. We turn now to that task. We examine relationships across the major spheres for which complementarities are posited by the varieties-of-capitalism literature. Taking the postulates of Hall and Soskice (2001a: esp. Figures 1.3 and 1.4) as the template, we examine the complementarities described above between labor relations and training systems and between corporate governance and inter-firm relations; and we consider the policy regimes associated with social protection and product market regulation where strong claims of complementarity with coordination in other spheres of the economy have been made (Estevez et al. 2001; Hall and Soskice 2001a). In each case, we are attentive to the type of claims the theory makes. In some cases, the claims about complementarities refer to relatively-formal institutions, such as the provisions of a regulatory regime. In others, they refers to an ensemble of institutionalized practices, such as patterns of inter-firm collaboration and types of corporate governance that cannot be associated with a single institution but have a specific character associated with distinctive types of coordination. One of the principal challenges is to find indicators for the relevant institutional dimensions, a large problem if more than a handful of cases are to be considered and we do not code them ourselves, a technique we have resisted in order to avoid biasing the tests. However, we have found indicators for the relevant types of institutional variation across the seven spheres where the varieties-of-capitalism approach suggests major complementarities are available. For labor relations and corporate governance, we use the same indicators employed in the preceding analysis. The others are as follows:

Social Protection refers to the level of support provided to the unemployed and to limitations on the right of firms to lay-off workers. We measure it by combining the indices of ‘unemployment protection’ and ‘employment protection’ devised by Estevez et al. (2001) using weights for each generated by the principal component that appears when a factor analysis is applied to the two indices. Higher values indicate higher levels of social protection.

Product Market Regulation refers to the limits placed on competition in product markets by the regulatory restrictions that national governments impose on businesses. The measure is based on an OECD survey of many types of regulatory practices combined into a composite measure through multi-level factor analysis by Nicoletti et al. (2000: 80). Higher values indicate product market regulations more restrictive of competition.

Training Systems are assessed with a view to establishing the extent of institutional support a nation provides for the development of vocational skills in young workers beyond what they secure in formal secondary or university education. In general, this entails apprenticeship schemes or training programs dependent on the collaborative involvement of firms. The measure is based on the principal component that emerges from a factor analysis on two variables: the number of pupils in vocational training as a proportion of those in general education and the mean scores on a literacy test secured by a sample of workers between the ages of 20 and 25 who left school before completing secondary education (United Nations

If this is correct, nations with high levels of strategic coordination in labor relations should provide more extensive support for vocational training outside formal education, while market coordination in labor relations is associated with lower levels of support.

H6. Complementarities of the type posited by this approach exist between the spheres of corporate governance and inter-firm relations.

If this is correct, where strategic coordination in corporate governance is more prevalent, inter-firm relations should be more collaborative; and, where market coordination dominates corporate governance, inter-firm relations should be more market-oriented.

H7. The policy regimes associated with social protection and product market regulation can be complementary to coordination elsewhere in the political economy

If this is correct, high levels of social protection and restrictive product market regulations are more likely to be found in nations where strategic coordination is more prominent in labor relations and corporate governance, while nations whose firms rely more heavily on market coordination are likely to have developed lower levels of social protection and less-restrictive product market regulations.

H8. Firm structures and strategies vary systematically across nations as firms develop structures and strategies to exploit the complementarities available with the institutional context for their principal spheres of endeavor.

If this is correct, where nations provide more institutional support for strategic coordination in labor relations, corporate governance, vocational training, and inter-firm relations, firms should tend to pursue more ‘cooperative’ strategies, managerial prerogatives should be more restricted, and employment tenures should be longer. Conversely, where institutional support for market coordination is higher, firm strategies should be less ‘cooperative’, managerial prerogatives higher, and employment tenures shorter.

Figure 2 summarizes our examination of these hypotheses. The boxes around ‘firm strategy’ represent the four spheres in which a firm coordinates with other actors to accomplish its principal endeavors. The two variables at the top indicate policy regimes relevant to this coordination. The lines between the boxes indicate the hypotheses about complementarities generated by the varieties-of-capitalism literature examined here. Using cross-national comparisons of all the cases for which we have relevant measures, we have calculated correlation coefficients indicating whether the presence of institutional practices of a particular type in one sphere are associated with institutional practices in adjacent spheres reflecting the complementarities posited by a varieties-of- capitalism perspective. This perspective predicts positive coefficients across the diagram. The results are impressive. The coefficients in Figure 2 are uniformly positive and relatively large. All are statistically significant at the .05 level. 16 The uniformity of the results is striking. Given that these predictions about complementarities flow from a

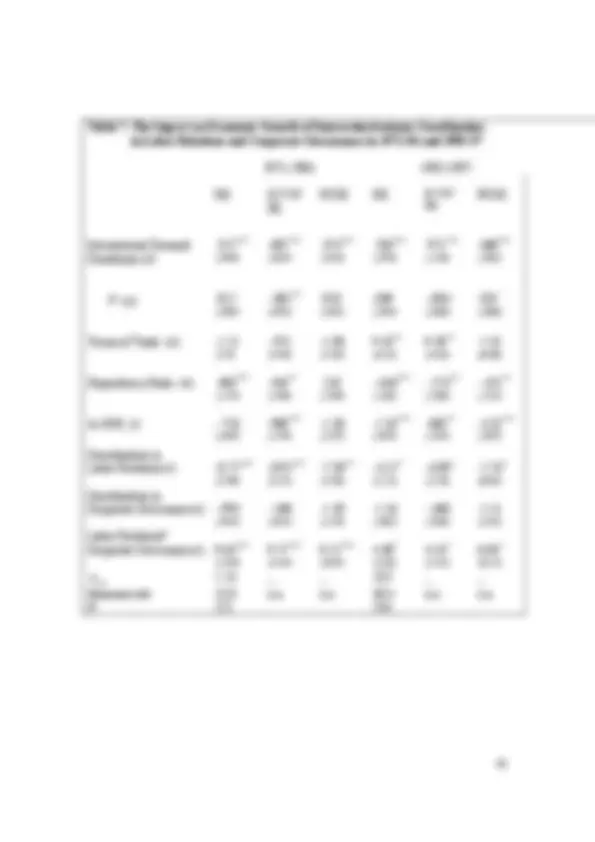

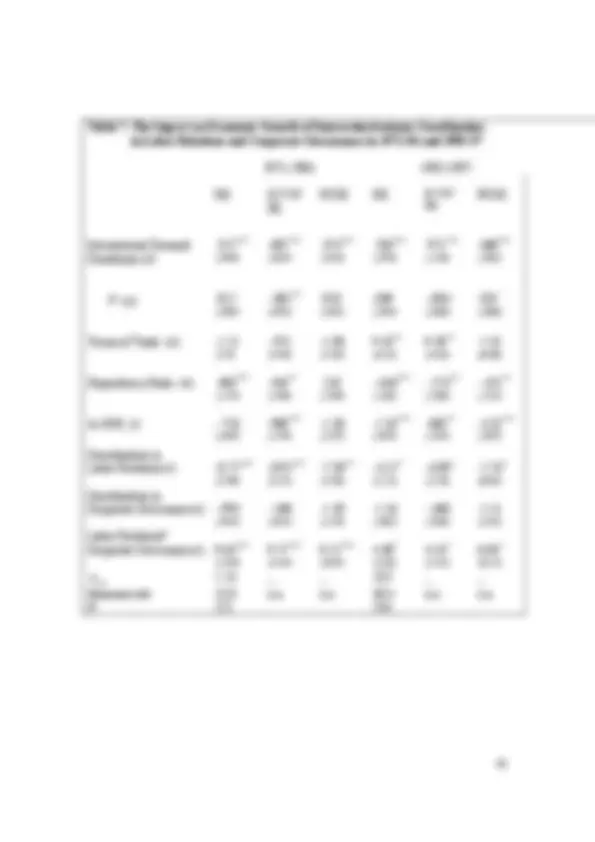

unified theory, each coefficient can be seen as a test of that theory, and it survives multiple tests. The kind of complementarities posited by the varieties-of-capitalism literature seem to be important features of the political economy. The patterns of firm strategy are also notable. Figure 2 suggests that firm strategy varies systematically with the institutional support available for different types of coordination in the four spheres central to corporate endeavor. Table 3 provides further evidence for this contention by comparing the relationship between three indicators for corporate strategy and national scores on the coordination index. In each case, there is a strong, statistically-significant correlation in the direction posited by the theory.

4. The Effect of Complementarities on Economic Growth

As we have noted, this examination of institutional congruence across political economies provides tests for complementarities that are 'soft' because it assumes that, if complementarities offering efficiencies are available, actors will develop institutions to take advantage of them. This is highly plausible. But efficiencies alone do not dictate institutional development. Similar institutional features could appear in a political economy because they are the product of common historical processes, without necessarily reinforcing the operation of each other. Pagano and Volpin (2000), for instance, argue that high levels of investor and employment protection originate in a corporatist bargain feasible where the political system supports coalition governments. If they are correct, this combination of institutions may be efficient, but its appearance cannot be attributed to that efficiency. Moreover, such analyses raise questions about the efficiency of complementarities for the economy as a whole. Some combinations of institutions may increase the returns to particular sets of actors, but in the form of rents that redistribute aggregate income, rather than raise it, and they may even lower it. By contrast, the varieties-of-capitalism approach posits institutional complementarities that are generally efficient, in the sense that they should increase income for the economy as a whole, even though they may also have distributive effects. For these reasons, it is necessary to go beyond the 'soft' tests hitherto employed. The varieties-of-capitalism view of complementarities should be subjected to ‘hard’ tests that assess, not only whether institutions tend to accompany one another, but whether their presence tends to improve economic performance. We turn now to that task. Our indicator will be rates of economic growth per capita, widely accepted as the best measure of overall economic performance and appropriate for testing postulates about general efficiency. Moreover, this measure provides an exceptionally hard test. Because aggregate rates of growth depend on the efficiency of the entire economy, particular institutions will have to make substantial contributions to it to increase aggregate rates of growth. We begin by taking up the most general claim of the varieties-of-capitalism literature that high levels of strategic (market) coordination in one sphere of the economy will be complementary to high levels of strategic (market) coordination in other spheres. This implies that rates of growth should be higher in countries where market or strategic coordination is high across spheres than in those where coordination is mixed or in those where either type of coordination is secured only at lower levels. We can assess this by

on dependent and independent variables that have been multiplied by an idempotent matrix to transform them into differences from their means, and a between-estimator generated by performing OLS on dependent and independent variables that have been transformed into ones reflecting the difference between panel means and the variable mean. The random effects estimator converges to the OLS estimator as the efficient estimate of the between-group variance component goes to zero, and to the fixed-effects estimator as the between-group variance goes toward infinity (Hsiao: 34-38). The model treats panel-specific effects as random disturbances, as they would be if the panels in the study represent a random sample from a larger population, and it takes the following form:

where Xit is a Kx1 vector of time- and panel-varying independent variables, Z (^) i is a Jx vector of panel-varying but time-invariant independent variables, and vit is an error term where ui are scalar constants representing panel-specific fixed effects and the error term, vit = u (^) i + wit such that: E(ui ) = E(wit ) = 0, E(ui wit ) = 0; E(ui u (^) j ) = σu^2 , if i = j and otherwise 0; E(wit wjs ) = σw^2 , if i = j and t = s and otherwise 0; and E(ui Xit ') = E(ui Zi ') = E(wit Xit ') = E(wit Z (^) i ') = 0. If the panel-specific effects and independent variables are still correlated even after the latter have been transformed, the random-effects model will be biased, and Hausman (1978) has produced a test for such correlation, based on the difference between the coefficients and covariance matrices of the fixed-effects and random-effects estimators. Since this test indicates potential bias in our random-effects model, we also develop a third set of estimates, employing an instrumental variables technique suggested by Hausman and Taylor (1981). It produces a standard fixed-effects estimator for all variables that vary over time and space. To produce coefficient estimates on the time- invariant variables, the technique utilizes the time-variant variables assumed to be uncorrelated with panel-specific effects as instruments in a two-stage least-squares procedure.^19 Table 4 reports the results of these three estimations. In all, the coefficients on coordination are significant, of the same sign, and of similar magnitude, increasing our confidence in the results. The significance and signs of the coefficients on C and C^2 indicate that the relationship between coordination and economic growth is non-linear. Using the fixed-effects model for the simulation, Figure 3 shows the estimated relationship between coordination and growth when the control variables are at their means. The U-shaped relationship is apparent. Where the institutional structure of the political economy allows for higher levels of market coordination or higher levels of strategic coordination, estimated growth rates are higher than they are when there is more variation in the types of coordination present in the political economy. These results suggest that the varieties-of-capitalism approach to institutional complementarities, built on the distinction between market and strategic coordination, has real merit. When complementary institutions are present across spheres of the political economy, rates of economic growth are higher. The institutional complementarities identified by this perspective appear to offer general efficiencies.

Of course, there is some question about how much of the improvement in growth observed as nations move closer to the poles of the coordination spectrum arises from the development of complementary institutions across spheres and how much from improvements to the coordinating capacity of institutions in each of those spheres. In order to check that institutional complementarities occur across spheres, we developed a second set of models to assess whether coordination in labor relations interacts with the character of coordination in corporate governance to affect economic growth as the varieties-of-capitalism literature predicts. This model has the following form:

i it it it it it

CG i

LR i

CG i

LR

(3) where CLRi represents the character of coordination in labor relations in country i and CCGi represents the character of coordination in its sphere of corporate governance, using the measures for each developed above (pp. 13-14), and controls as in our first set of estimations. This model is used to test the following hypothesis implicit in the varieties- of-capitalism perspective:

H10 : When there are higher levels of market (strategic) coordination in the sphere of labor relations or corporate governance, rates of economic growth increase as the level of market (strategic) coordination in the other sphere increases.

If this is correct, the interaction term in the model, C LRi * CCGi , should be statistically- significant and positive. A significant coefficient indicates that the impact of coordination in one sphere is dependent on the character of coordination in the other sphere, and a positive coefficient indicates that analogous types of coordination in the two spheres raise rates of growth.

Once again, we estimated the model using three specifications to cope with the potential for bias arising from collinearity between the time-invariant measures of coordination in labor relations and corporate governance and panel-specific effects.^20 Table 5 reports the results of these estimations. The parameter estimates are broadly stable across the three models. The coefficient on the interaction term is positive, of considerable magnitude, and statistically-significant. This tends to confirm the presence of substantial complementarities between the spheres of labor relations and corporate governance of the sort postulated by varieties-of-capitalism theory. Using the fixed-effects model for the purposes of simulation, Table 6 reports the rates of growth that could be expected under different combinations of coordination in labor relations and corporate governance when the control variables are at their means. Although one should cautious about attributing significance to point estimates in such simulations, the broad patterns in the table are revealing. 21 They show clear evidence of interaction effects between the character of coordination in the two spheres. Rates of growth are highest where competitive markets coordinate both spheres or where institutional support for strategic coordination is high in both. Where labor relations are strategically-coordinated, substantial efficiencies seem to be available from strategic- coordination in the sphere of corporate governance. Where corporate governance is

efficiencies available from existing combinations of institutions. If the potential for productivity growth is lower in services, the growing importance of that sector may undercut the efficiency gains available from systems of coordinated wage bargaining or social protection that compress wage differentials and sustain high wage floors (Iversen and Wren 1998; Scharpf and Schmidt 2000). In epochs of rapid technological advance that increase the opportunities for radical innovation, the market-oriented complementarities of liberal market economies, which lend themselves to this type of innovation, may offer higher returns than they otherwise would relative to those of coordinated market economies, which are better at incremental innovation (Hall and Soskice 2001a: Hall 1997; Soskice 1994).^22 International integration may alter the value of an economy’s comparative institutional advantages by improving access to production sites offering other kinds of complementarities (cf. Frieden and Rogowski 1996). If developments such as these alter the returns available from existing institutions, pressures to change those institutions are likely to increase. It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider the effects of each secular economic development on institutional stability. However, a summary impression can be formed by comparing the economic impact of these complementarities in recent years with their impact in an earlier period. For this purpose, we estimated the models for the economic impact of complementarities between coordination in labor relations and corporate governance over two time periods, 1971-84 and 1985-97 (see equation 3). Once again, three estimation techniques were employed to accommodate the potential for panel specific effects, although a λLM indicates that estimates based on panel-corrected standard errors are relatively unbiased by such effects. These estimations are used to test the following hypothesis:

H11 : Secular economic developments over the past two decades have not altered the efficiency of the institutional complementarities posited by the varieties-of-capitalism perspective between labor relations and corporate governance.

If this is correct, the coefficient on the interaction term between coordination in labor relations and corporate governance, CLRi * CCGi , should be positive and statistically- significant across both periods.

The results of the estimation are presented in Table 7. For the 1971-84 period, the coefficients on the interaction term are positive, statistically-significant, and larger than those for the entire 1971-97 period (see Table 5). In the 1985-97 period, the coefficients on the interaction term remain positive, but they diminish in size and just miss statistical significance at the .05 level. The coefficients for all the institutional variables lose significance in the more recent period. These findings suggest that the hypothesis should be rejected. Institutional complementarities with a large impact on levels of economic growth in earlier decades do not show as much impact on rates of growth in recent years. Two broad lines of explanation could account for this result. Secular developments may have reduced the returns available from these complementarities. Alternatively, the complementarities may still be operative but their impact on cross- national differences in growth overwhelmed recently by factors for which we do not control in these equations. The latter could include cross-national differences in economic policy, confidence effects arising from asset booms, or technology races that

privilege first movers. We cannot currently discriminate between these explanations. However, these results lend some credence to the view that secular economic changes may be shifting the effectiveness of existing institutions. If so, pressures to change existing institutions should increase.

Political Dynamics In this context, the political dynamics of institutional change become especially important, and the varieties-of-capitalism literature advances a particular view of such dynamics. In general, its view is built on the contention that the market-oriented settings of liberal market economies encourage firms, holders of capital, and workers to invest in switchable assets, whereas institutional support for strategic interaction in coordinated market economies encourages higher levels of investment in specific assets (Hall and Soskice 2001a; Iversen and Soskice 2000). In the former, fluid markets that facilitate the transfer of resources among uses enhance the returns to switchable assets. In the latter, better institutional support for the formation of credible commitments reduces the risks of investing in co-specific assets whose value depends on the cooperation of others and that cannot readily be switched to other uses if that cooperation is not forthcoming. This divergence in patterns of investment is significant because each generates a different politics. In the face of an exogenous shock threatening returns to existing activities, holders of mobile assets will be tempted to ‘exit’ those activities to seek higher returns elsewhere, while holders of specific assets have higher incentives to exercise ‘voice’ in defense of existing activities (Hirschman 1964). The argument is analogous to the distinction drawn between a Hecksher-Ohlin world, where factors are mobile and shifts in relative prices (of the sort associated with increasing economic openness) generate conflict between the holders of basic factors, such as capital and labor, and a Ricardo-Viner world, where factors of production are sector-specific and shifts in relative prices inspire inter-sectoral conflict that unites employers and workers in defense of sectoral interests (cf. Hiscox 2001; Frieden and Rogowski 1996; Alt et al. 1996; Rogowski 1989). From this perspective, the varieties-of-capitalism literature argues that the political response to contemporary economic challenges will vary across liberal and coordinated market economies. In LMEs, the response will be highly market-oriented. When returns to existing activities are threatened, holders of mobile assets, such as workers with general skills or owners of capital on fluid equity markets, will tend to shift to new activities. In general, they will be interested in rendering markets even more fluid. Where nations respond to shocks by relying on markets to adjust prices and wages, however, substantial shifts in the distribution of income may occur, including increases in income inequality. Such distributive effects are likely to increase conflict between those with and without market-power, namely conflict of a 'class' character, notably in arenas responsible for the regulation of income, such as the sphere of industrial relations. In coordinated market economies, by contrast, the varieties-of-capitalism perspective expects similar economic challenges to inspire a different political response. That response will be mediated by higher levels of asset specificity. When returns to existing activities are threatened, holders of specific assets, such as workers with industry-specific skills and owners of enterprises deeply-invested in co-specific assets, will find it difficult to shift to new activities. As a result, they will be less inclined to