Download Sex Inequality at Work: Promotions, Authority, and Work-Family Conflict and more Slides Psychology of Sex in PDF only on Docsity!

Lecture Note 6

Sex Inequality at Work: Promotions;

Paid Work and Family Work

Sex Differences in Promotion (1)

- The general trend: the critical period of promotions: early years of a career. Men are promoted at a faster rate during those years (in the early 1980s, men average 0.83 promotions compared to women’s 0.47; the promotion gap narrowed considerably in recent years)

- Education:

- High school or less than high school education: women are more likely than man to be promoted

- College graduates: 35% men vs. 29% women being promoted

- Postgraduates: 34 % men vs. 21% women being promoted

- Marital Status: married men had greater opportunities than married women

- Parenting: fathers of preschoolers had greater opportunities than mothers of preschoolers

Sex Differences in Authority

- Authority at work: exercising authority means having

legitimate power to mobilize people, to get their

cooperation, and to secure the resources to do the

job.

- In a bureaucracy, authority resides in the job, not in

its occupant’s personal qualities. (i. e., Managers

have the job authority to set rules, but secretaries do

not)

- The glass ceiling in management: the higher the level

of authority in an organization, the less likely women

are to be represented.

Glass Ceiling in Different Occupations (1)

- Private Works:

- Catalyst’s research (2000): in all Fortune 500 companies, less than 13% of the corporate officer slots were held by women

- The top 10 highest-earning companies, women’s share of officer positions ranged from 0%-31%

- Women being CEO (Chief Executive Officer), chair, vice chair, president, chief operating officer, and the like: only 5 women in all Fortune 500 companies in 2001.

- Women in the boards of directors: 12% in the Fortune 500 companies

Glass Ceiling in Different Occupations (3)

- Women are underrepresented in the jobs in the professions, the military, and the unions

- E. g. in the field of law, women were far more likely to be law firm associates (39%) than law firm partners (15%)

- E. g. Medical doctors: female medical school graduates between 1979 and 1993: made up only 10% of medical school faculty

- E. g. In the military, women’s representation in the officer ranks was about equal to their representation in the enlisted ranks, but female and minority officers were concentrated in less-prestigious administrative and supply areas and underrepresented in tactical operations

- E. g. the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) only started to hire female agents from 1972. Now 92% of the highest ranks were men.

Sex Differences in Opportunities to

Exercise Authority (1)

- “Glorified secretaries”: women with managerial titles but not the responsibilities and authority that usually accompany the titles. In other words, in some cases that the boss promoted women to decision-making position just to put them as “tokens”. They were not expected to really exercise the authority.

- When exercising authority, women in customarily male jobs would be resisted by their coworkers.

- “hostility toward members of the other sex”, particularly the feeling of being threatened by women with power of men in traditional men’s work

Explanations for the Promotion and

Authority Gaps

- Sex-segregated Internal Labor Market

- Sex Differences in Human Capital

- Sex Differences in Social Networks

- Organizations’ Personnel Practices

“Internal Labor Market” (1)

• “Internal Labor Market”: the mechanism that

coverts segregation into a promotion gap.

• “Job ladders”: promotion or transfer paths

between lower- and higher-level jobs.

• Internal labor markets comprise related jobs

(or job families) connected by job ladders.

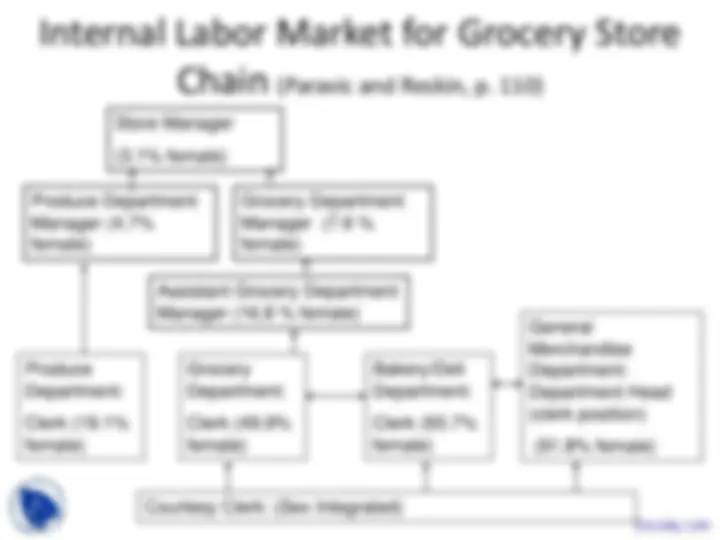

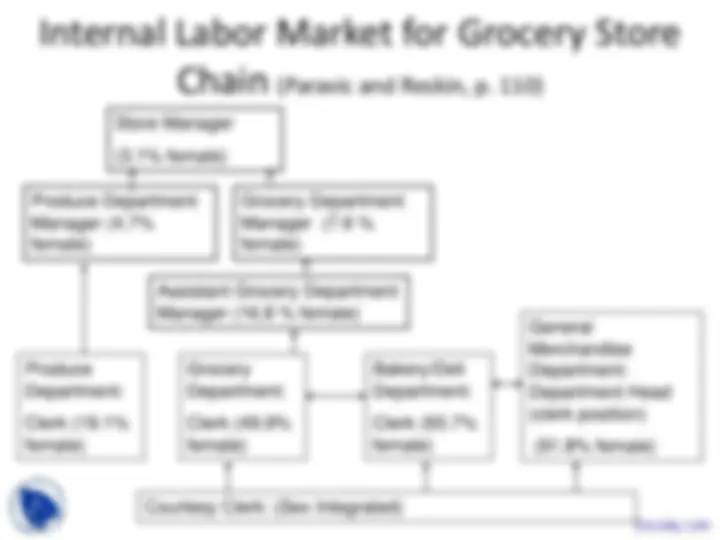

Internal Labor Market for Grocery Store

Chain (Paravic and Reskin, p. 110)

Courtesy Clerk: (Sex Integrated)

Store Manager (3.1% female)

Produce Department Manager (4.7% female)

Produce Department:

Clerk (19.1% female)

Grocery Department Manager (7.6 % female)

Assistant Grocery Department Manager (16.8 % female)

Bakery/Deli Department: Clerk (93.7% female)

General Merchandise Department: Department Head (clerk position) (91.8% female)

Grocery Department: Clerk (49.9% female)

“Internal Labor Market” (3)

- Establishment segregation: large organizations have the

resources to create internal labor markets (and promotion opportunities). But women tend to concentrate in small, entrepreneurial firms and nonprofit organizations.

- Women’s share of top leadership jobs affects other women’s

opportunities to promote and exercise authority.

- Women’s share of non-managerial jobs: if companies fill

managerial jobs by promoting people from the insider pool, a strong representation of women in non-managerial positions increased female employee’s share of managerial jobs.

Human-Capital (1)

- The theory: Women as a group are under-represented at the top of career hierarchies because they lack the experiences needed to advance into positions that confer authority

- The theory should be revisited by emphasizing that women alone should not be blamed for their receiving less training and having less experience. Oftentimes their opportunities are blocked by organization’s personal policies and practices.

- Remedies: 1. Adding women at lower levels where they can gain experience and enter the pipeline leading to future high- level jobs

- The removal of barriers that block women’s access to training and experience

Sex Differences in Social Networks (1)

- In the following circumstances, filling jobs through social networks tends reproduce the characteristics (such as the under-representation of women in managerial positions) of the existing workforce:

- At the highest levels, most organizations are male dominated.

- People’s social networks tend to comprise others of the same sex, ethnicity, and race.

- If the pool of people being considered is made up of members of decision makers’ social networks, women usually will be disadvantaged.

- The fact: most managerial jobs are filled through informal networks

Organizations’ Personal Practices (1)

- Decision makers’ sex stereotypes reduce women’s

chances of being promoted

- Research of Perry, Davis-Blake and Kulik (1994)

shows that when women are already fairly well

represented in the higher ranks, decision makers

tend to act in a more gender-neutral way in

conferring promotions, resulting in less bias in favor

of men.

- “Homosocial reproduction”: managers’ selection of

workers for jobs based on their social similarity to

managers

Organizations’ Personal Practices (2)

- Remedies:

- Organizations can reduce the promotion and authority gaps

by replacing informal personnel practices with formal ones that restrict opportunities to act on bias. Bureaucratic practices discourage favoritism;

- Use formal criteria to ensure that decisions are based only

on relevant information for each candidate and not on casual impressions or hearsay;

- Raise the price (such as fines and other financial sanctions)

that employers pay to discriminate;

- Legislation can reduce the authority gap when it is

implemented and enforced.