Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

Insights from the author, a university professor and communication expert, on how to develop a powerful, clear, and resonant speaking voice. It covers fundamental techniques, breaking bad habits, and improving diction, rate, and inappropriate voice production. The author emphasizes the importance of proper breathing, posture, and resonance.

What you will learn

Typology: Study notes

1 / 44

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

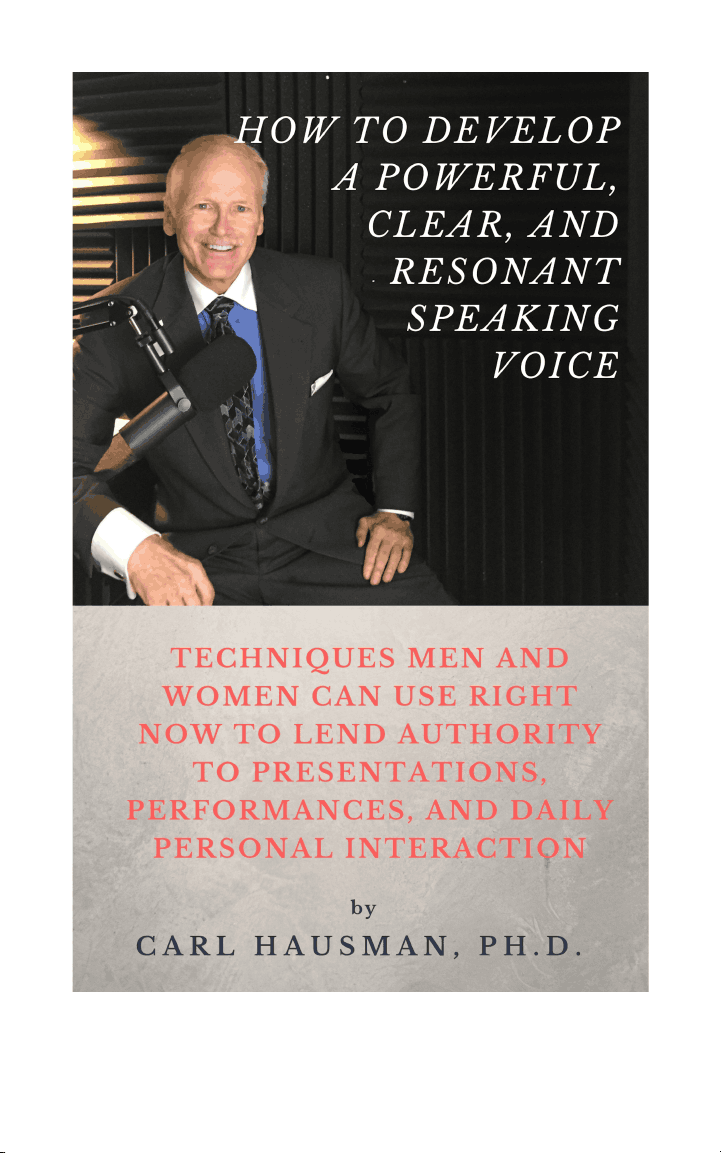

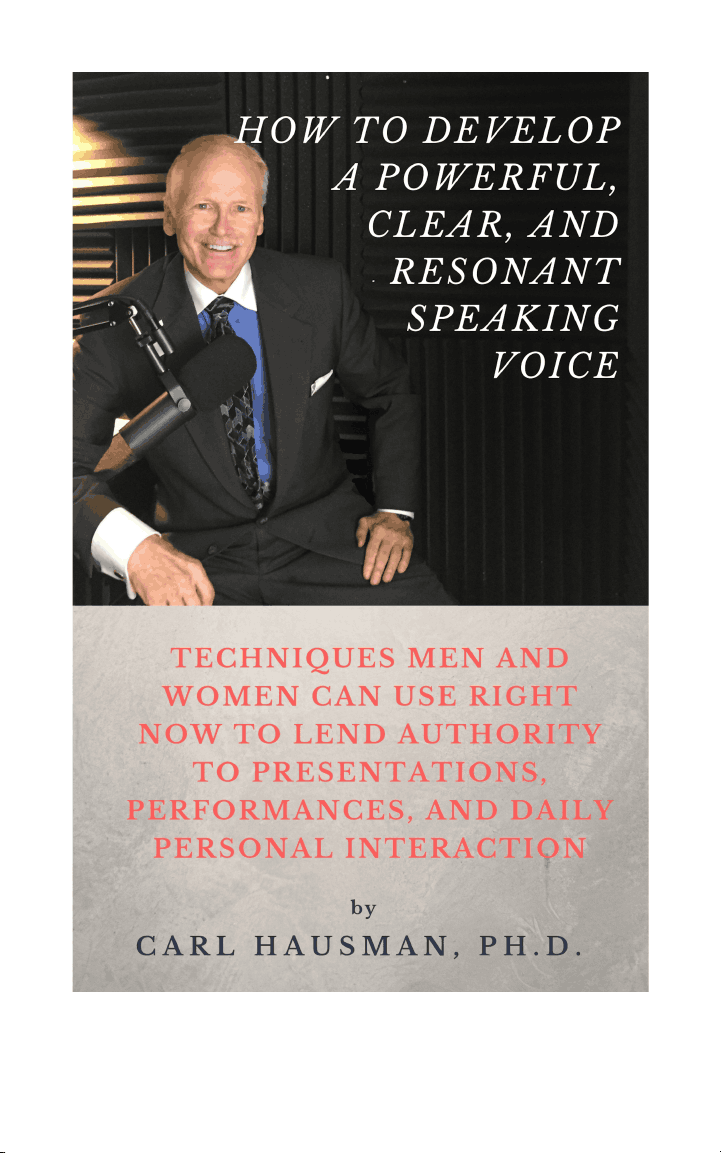

INTRODUCTION Welcome to my book about developing a powerful, clear, and resonant speaking voice. This book is for men and women, and it’s all about using your voice to lend authority to presentations, performances, and daily personal interaction. Let’s begin by clearly identifying what you’ll get from this work. First, as you’re investing your time – the most important commodity anyone possesses – you probably wonder what qualifies me to create this course. I’ve worked on both ends of the speaking business, as someone who makes a living with my voice and as someone who teaches and writes about communication. I’m currently a full-time university professor, and I’m the author of several books about communication, including a textbook on radio and television announcing and one of my latest books, Present Like a Pro, which is about simple techniques for improving public speaking. Also, I’ve narrated quite a few audiobooks, am an experienced public speaker, and spent many years as a television and radio announcer. You can find all this with a Google search, so there’s no point in belaboring it. Suffice it to say that I’ve invested a lot of time and energy researching what works for me and what works for others.

CHAPTER 1 : WHAT YOU’LL GET FROM THIS BOOK You’ve come to this course because you think a better speaking voice is important, and you’re right. Fair or not, the sound of your voice – your tone, your clarity, your timbre – is part of that whole package of criteria on which people judge you. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal reported about research showing that the sound of a speaker’s voice matters about twice as much as the content of what he or she is saying. But can you change your voice? Isn’t having a good voice like being tall – you either are or you aren’t and if you’re not there’s nothing you can do about it? Not exactly. It’s undeniably true that some people are simply born with good voices, but even those “naturals” worked on their tone and delivery and made both better. They may not have taken a class or read a book (though many did), but if they were in broadcast they heard recordings of themselves, or if they were public speakers, they noted audience reaction and feedback. One way or another, good speaking voices are usually made. They are made better by application of what are essentially some simple techniques. I make my living, in part, with my voice, and like many voice professionals I’ve combined formal training with feedback I’ve received from others and with my own observations. ‘ One bit of advice that I’ll give out right at the beginning of this book is that the simple act of recording yourself and playing the recording back gives you enormous insight into voice improvement. You may not consciously know the thousand little

This course is divided into three basic sections. We’ll start by looking at some fundamental and fundamentally simple techniques that you employ right way – quick and easy changes in how you breathe and support your voice, how to stand, and how to inject some resonance and carrying power in your voice. Next, we’ll focus on breaking bad habits, including voice patterns – repetitive ways you structure your speaking – and problems with diction and rate. The course concludes with a program of exercises and methods for life-long improvement and protection of your voice. I’d like to conclude this chapter by reinforcing the fact that how you sound does matter. I was struck by an article I read recently concerning “uptalk” – that extremely annoying voice pattern where every sentence ends with a rise in pitch. I’ve always thought that uptalk just kills a speaker’s credibility and a survey of 700 managers found that almost three quarters of them found uptalk “particularly annoying,” and 85 percent said it was a sign of “insecurity or emotional weakness.” Wow. More on uptalk later but I think you get the point. And the equation works in reverse. We all know vacuous Ted Baxter-type speakers who look and sound credible…and people believe them – regardless of the substance or lack thereof of what they actually say. This sounds obvious but your voice speaks for you. Literally. It is your calling card in an increasingly noisy and fast-paced world. You need every advantage you can to communicate your point.

A good, clear, resonant, confident voice is an important tool for commanding the attention and respect you deserve.

more actively engaging that sheet of muscle behind the whole process, the diaphragm. More on that in a second, but first let me clarify that what we are talking about is nothing more than a method of breath control that gives you a bigger air supply and, more importantly, a steady flow of air for vocal support and power. So…what is this mysterious “diaphragm?” It’s a sheet of muscle that covers the bottom of the breathing area of your chest. Moving it down sucks air in, nd moving it up blows air out. It’s as simple as that. If you let the diaphragm do its work you can really get some power behind your voice. The figure below shows the basic anatomy of the diaphragm and chest area.

Where most people go wrong is that the equate taking a big breath with expanding their chest. But the chest is where the lungs are, and in point of fact they have nothing to do with expelling air. They’re just filters to get the oxygen out of the blood. Take a look at the picture. See what I mean when I say that air support figuratively comes from the stomach? Throwing out your chest is actually counterproductive because it diverts your attention and effort away from the proper area to expand – the abdomen.

Flex your knees just a little. This is a posture taught to me by David Blair McCloskey, a famous vocal coach who has worked with such notables as President John F. Kennedy, actor Al Pacino, and actress Ruth Gordon. McCloskey was an operatic baritone, and also taught this posture to opera singers. Why does this posture enhance the voice? Simply because it allows for the freest expansion of the diaphragm.

There’s no mystery here: Take much deeper breaths, allow the abdomen to expand, making sure you don’t expand the chest or the short ribs, and push the air out from the diaphragm. Put your hand a little below the solar plexus and push in gently, aiding the process. You’ll feel what I mean. And more importantly, you’ll hear what I mean. Now that you know what that sensation feels like, replicate it. Practice it. I know I sound like an infomercial salesman here, but I would be remiss if I didn’t say, “wait, there’s more!” But – there is more. Diaphragmatic breathing not only helps with voice production but also with relaxation. If you’ve ever engaged in any martial arts training you know that deep breathing from the diaphragm is often a part of the process. Mediation also involves deep, slow breathing. Another benefit: Breathing more deeply and taking in a full tank of air forces you to slow down your rate of speech a little because you have to take time to breathe. Almost every speaker can benefit from slowing down a little. And one more thing: If you take rapid, shallow breaths, you’ll sound nervous – even if you’re not. The simple act of forcing yourself to take less frequent, much deeper breaths makes you appear more confident. And when you appear more confident you set up a feedback loop with the audience and you actually become more confident. So, let’s put it all together. This is a simple, straightforward process. It’s not always easy, because any new habit takes time to develop, but all you have to do is remember that your basic purpose is to produce a more powerful and more steady column of air. To do this, allow the diaphragm to expand. Don’t expand your chest. Expand the abdomen. Keep your back fairly straight and tuck your hips in to allow for full, comfortable expansion.

CHAPTER 3 : DEVELOP RESONANCE BY “USING YOUR HEAD” The character that gives a voice a round, ringing quality is called resonance. A resonant voice is not necessarily a deep voice. You may remember, for example, Mike Wallace, who spoke in a high register but had a marvelously rich vocal quality. In fact, let’s take a minute and discuss the whole concept of deep voices. We’ve come to associate basses and baritones with famous male speakers, and to a lesser extent some people listen favorably to a deeper female voice, which would be in the register we call alto. This preference for male basses and baritones and female altos may have come about by accident when deep-voiced announcers began to dominate the airwaves. But, as a side note, it’s interesting to learn that in the early days of broadcasting a high male voice was preferred – it was thought that a tenor was the appropriate voice for cutting through static. My point is there’s no right or wrong range, although to avoid shrillness it’s often a good idea for speakers to drop their pitch a little…something we’ll deal with a little later. But for now, simply remember that a pleasing voice is more a product of resonance than pitch. Resonance gives your voice that ringing attribute that not only sounds good but helps – along with proper breath support – your voice to carry. We call this “head resonance,” and here’s why.

Your vocal cords make only a little squeak – just as the reed in a wind instrument, such as a clarinet, produces a squeaky duck call if you just blow into the mouthpiece when it’s not attached to the instrument. But when you put the mouthpiece on the clarinet, you get a very powerful sound, even without any of the finger holes closed. Why is that? It’s not really a function of length. We’re only lengthening the path of the air by about four inches if none of the finger holes are closed. What produces the distinctive mellow sound of the clarinet is the vibration of a column of air and the instrument itself. That’s where the power and the ringing sensation comes from. A string instrument does the same thing. The vibration of a guitar string would be barely audible if it didn’t take place right over the sounding hole of the instrument. The wood and the air inside set up resonant vibrations. Remember, the vocal cords are small flaps of tissue. They’re generally less than an inch long. You can see an approximation of what they look like in the drawing below.

Sometimes this is called “mask resonance” because the area that produces the vibration looks like a Lone Ranger mask. “Head resonance” and “mask resonance” mean the same thing. So – how do you cultivate that head resonance? Start by humming. Use the breath support you learned about in the previous chapter. You can feel the vibration. Try to move the epicenter of that vibration – that buzzing feeling – to the center of your lower forehead. One way to coax that sensation to the right area is to let a little more air into your nose. Air traveling through the nasal passages is good, in the right proportion. You do want a slightly nasal sound, although that term is probably the opposite of what you’re thinking. Most of us picture a nasal voice as what you get when you have a cold, but that’s actually “de-nasal.” In de-nasal situations, the air can’t get up in there and vibrate – which is precisely why your voice doesn’t carry and sounds muffled when you’re stuffed up. It’s all about getting the voice higher up in the head. You may remember an actor named Alan Ladd. He’s most famous for the movie “Shane.” He had a self-taught vocal technique, and he explained it this way: He said he “bounced his voice” off the roof of his mouth. That’s a pretty good way to explain it: Get that voice up in the head. Let it resonate. I’d suggest you go to YouTube and watch a little of Alan Ladd. You’ll notice that his voice is magnificent. It is clear, always powerful, and it is not very deep at all.

That’s the effect you want. Women should listen to Judi Dench, whose voice is a little on the deep side but actually gets its distinctive quality by being wonderfully round and resonant. Along the same lines, observe the ringing tones of Catherine Zeta-Jones, or Helen Mirren. That’s the effect you want. There are some other factors in resonance, and some techniques you can put to work right way. One method is to slightly exaggerate the “m” and “n” sounds at the end of a sentence. Don’t get carried away, but land on them it little harder and hold them a little longer. Actually, this is also a good technique for avoiding saying, “uh.” When you feel an “uh,” coming on, hold the last sound you spoke for a few fractions of a second more. Substitute that sound for the “uh.” As mentioned, half the battle – maybe more than half – is keeping that column of air steady. You can’t have head resonance without vocal support, so keep practicing your diaphragmatic breathing. Finally, it’s hard to be resonant and tight-throated and the same time. Constriction in the vocal chain quite naturally constricts the voice. Relaxation of the vocal apparatus is a topic unto itself, and will be dealt with in an upcoming chapter. In summary: Hum, and practice centering that tone. Humming is great because it also loosens up the vocal apparatus. Hum, and get the sensation of that buzzing in the lower center of your forehead. There’s nothing mystical about this – it’s simply a matter of getting the open areas in the mouth, throat, nose and head more involved in allowing the sound to resonate.