Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

This handbook serves as a guide for our centres on how to work with families and friends so they can provide the appropriate support for the young people in ...

Typology: Study notes

1 / 24

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Family and friends

inclusive practice

handbook

Our aim is to provide a simple guide that will prompt, support, encourage and embed family and friends inclusive practice at all levels of headspace in a form that is appropriate for each young person. headspace uses the term ‘family and friends’ rather than ‘carers’. This is in response to advice from its National Family and Friends Advisory Committee. headspace believes the use of this term encourages all people involved in a caring role to engage with the service and seek advice and support. The support networks of young people vary across stages of development and may also vary by social and cultural background. There are many different types and configurations of family and friends, including: all types of families (nuclear, extended, blended, single-parent, heterosexual and same-sex couples); non-parental care-givers (partners, foster-parents, grandparents, god-parents, adoptive parents, other family members); and significant others (friends, teachers, mentors). In maintaining a broad definition for the family and friends involved in a young person’s care, headspace is committed to an inclusive approach which recognises that the boundaries for describing those important in a person’s life are varied and flexible. The development of this handbook was a collaborative effort. The quotations featured throughout the document were written by Jess, one of the many youth advisors to headspace , and draw on her direct experience. Her contribution is reflective of the commitment of headspace to engaging with young people at all levels of service delivery to ensure that we remain youth friendly and youth focused. The hope is that this guide will inspire headspace centres and programs to engage with the family and friends of young people seeking support and by doing so, promote the best possible recovery outcomes for young people.

Young people between 12 and 25 years of age tend to be living with family members, and if they experience significant mental health difficulties it is often their family members who become their primary carers. Even when young people are living away from home they can still have significant contact with their families, and may continue to rely on them for support and guidance. Data from Mission Australia’s Youth Survey 2013 indicates that young people rely significantly on their family and friends for advice, with 68% reporting they seek advice from friends, 60% from parents and 51.6% from relatives and family friends^1. Young people are most likely to talk to family or friends as the first step in help-seeking^2 , and family and friends are often the first to notice a change in a young person’s emotions or behaviour that may signal the onset of a mental health or substance use problem. They also frequently encourage the young person to seek help or attempt to access help on their behalf. headspace data show that almost half of young people are most influenced by their family or friends to attend headspace , primarily family^3. We know from research that involvement of family and friends in a young person’s mental health treatment can contribute to reducing the incidence of relapse, improving adherence to treatment, improving family functioning, increasing periods of wellness, and improving the young person’s quality of life and social adjustment^4. Engaging with the family and friends of young people acknowledges the important role that these people play in the young person’s life. It also ensures that family and friends are sufficiently supported themselves to care for the young person, and that the support they provide is consistent with that of the young person’s treating team.

(^1) Mission Australia. Mission Australia Youth Survey 2013. Accessible at www.missionaustralia.com.au (^2) Rickwood, D.J., Deane, F.P., & Wilson, C. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, 2007. 187(7): p. S35–39. (^3) headspace centre client data April 2013 – March 2014, main influence at first visit to centre (^4) Pitschel-Walz, G., Leucht, S., Bauml, J., Kissling, W., & Engel, R. R. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalisation in schizophrenia – a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2001. 27(1): 73-92.

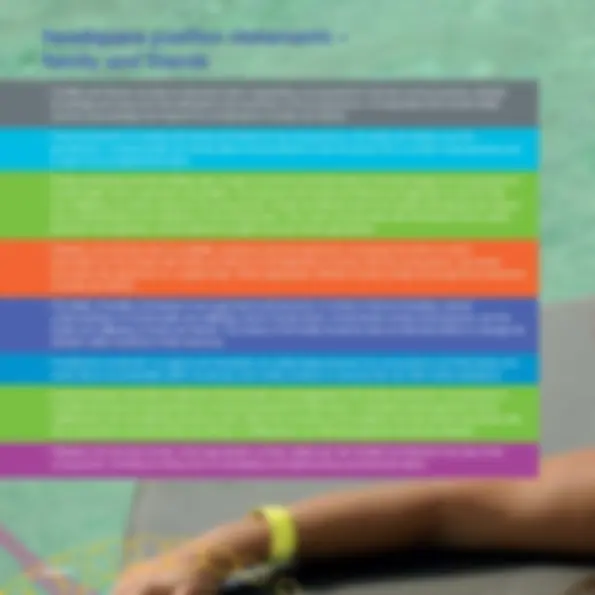

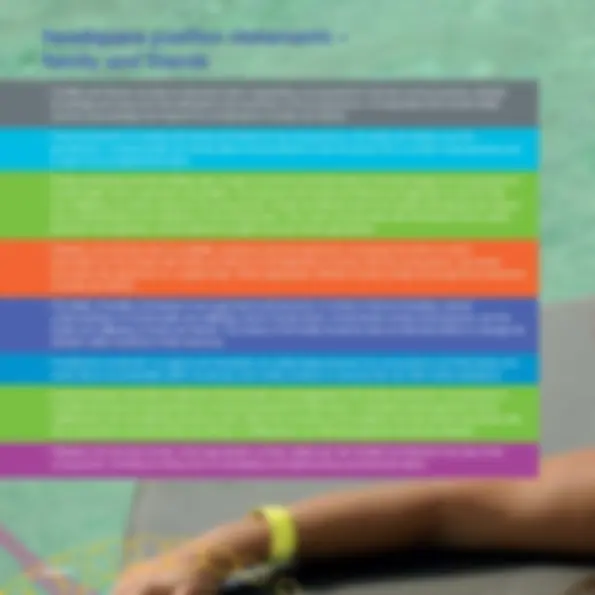

headspace position statements –

family and friends

Page 6

Understanding the family

dynamic

Understanding the configuration and dynamics of the family and network of supports around a young person helps to contextualise their relational experience and their behaviour, and provides a fuller understanding of their presentation. Any work with a young person should therefore include an assessment of the young person’s family of origin, family and developmental history, past and current living situations, intimate relationships and other significant relationships including their friends, teachers or mentors. This information does not have to be collected in one session, however, or at the first point of contact. It may be more appropriate to build up a picture of a young person’s family over time, as they become familiar with their treating team and feel more comfortable sharing information.

The support networks of young people are varied and will differ across cultures and at different stages of development. While for many young people, their primary supports will consist of their family and significant others with whom they live, this should not be assumed as holding true for all young people. Adopting a position of respectful curiosity, listening to how the young person describes their relationships with family and friends, and constructing a genogram in collaboration with the young person can be helpful strategies in building a good understanding of their family and support network.

Page 8

Page 7

Page 9

Desire for privacy Fears of being blamed for the young person’s problem

Feeling unsure or under-skilled in working with families/friends

Concerns about getting in trouble, disappointing or burdening family/friends

Geographic distance from the service

Regarding work with family/friends as being outside their role

Stigma around the disclosure of mental health difficulties

Time constraints, inflexible work hours

Time and resource constraints

Conflictual family relationships

Frustration with the young person, feeling overwhelmed

Fears of being overburdened by requests and information

Fears that others won’t understand or will be dismissive of their difficulties

Stigma surrounding mental illness and mental health services

Inflexible funding sources

Lack of knowledge of family support services

Negative community perceptions of mental illness -perpetuated by stigmatising language and labelling in the media

Concerns about breaching confidentiality

Lack of knowledge of family support services

Assumption that young person doesn’t want to involve their family or friends

Belief that family is to blame or is perpetuating the problem

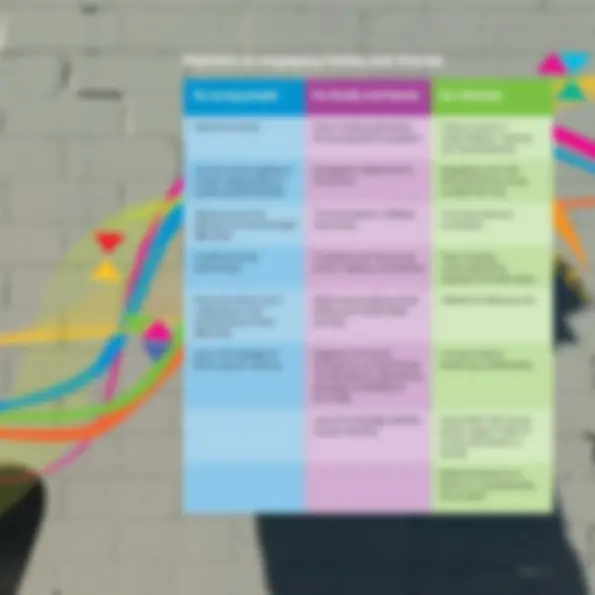

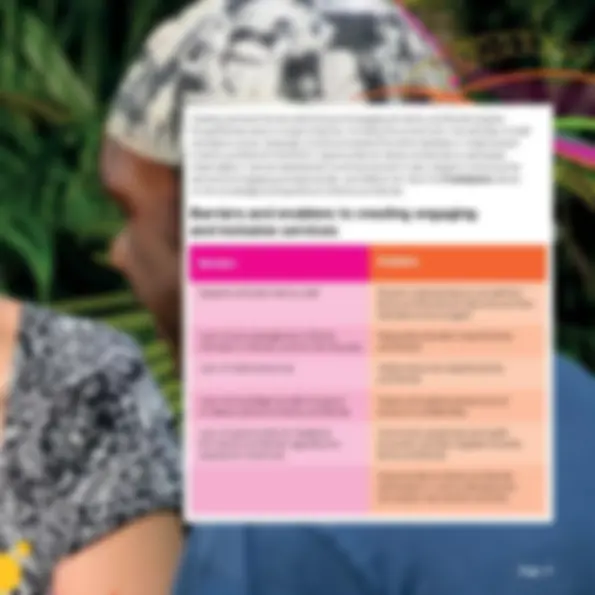

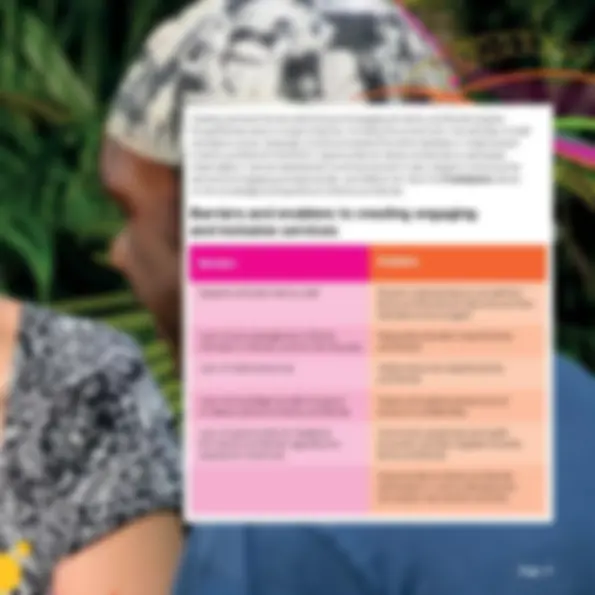

Barriers to engaging family and friends

Talking to young people

Finding ways to talk to young people about having their family and friends involved in their treatment is important in helping to break down some of the barriers that exist, both from the perspective of the young person and clinicians themselves.

The following tips may be helpful in talking to young people about involving their family and friends:

Recording: Make clear notes in the young person’s file about the types of information they have and have not consented to sharing with family and friends. This is important in terms of ensuring the young person’s wishes are followed and maintaining their trust Transparency: Encourage family and friends to talk with the young person openly about the information they’d like to know and the contact they’re having with the treating team. It’s preferable that young people and their family and friends are able to communicate about these things, even if it’s difficult or if they have differences of opinion. Be clear from the outset with young people about the limits of confidentiality and the situations where information may need to be provided to others.

Confidentiality is an important issue for a number of reasons, including the need for staff to uphold service commitments, the legal rights of a young person to privacy, the desire of those supporting the young person for information, and the relationship between maintaining confidentiality and gaining the trust of young people. headspace staff must also operate within the legal and professional frameworks that exist both nationally and at the relevant state level.

headspace provides a confidential service with clear exceptions around risk, however this should not lead to an assumption that in the absence of risk family and friends will not benefit from being informed of or involved in a young person’s treatment. Fears around breaching confidentiality should also not prevent staff members from encouraging the involvement of family and friends where appropriate. Our approach needs to consider the needs of young people to privacy, their need for support and protection at times by their family and friends, and the responsibilities of families given the age and developmental stage of the young person.

Some important work practices around confidentiality include:

Consent: A young person should be explicitly asked at the earliest appropriate opportunity about whether they give consent for family or friends to be provided with information about their treatment, and a discussion had about the types of information they are happy or not happy to have shared. Partial consent is still useful and may be appropriate depending on the young person’s age.

Information giving: If family or friends contact about a young person, information should not be given without getting consent in advance.

Even when a young person has stated their wish that information should not be disclosed to their family or friend, there are still ways of engaging and supporting their family and friends.

The following responses may be helpful when talking to family and friends:

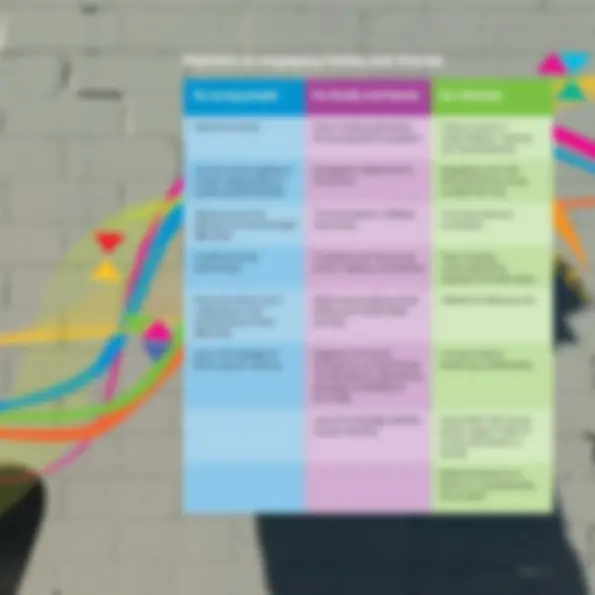

Creating services that are welcoming and engaging for family and friends requires thoughtfulness about a range of factors, including the environment, the attitudes of staff, workplace culture, language, and the processes that either facilitate or create barriers to family and friend involvement. Opportunities for family and friends to participate meaningfully in service development and improvement is also integral to ensuring that services are engaging and appropriate, and reflects the value that headspace places on the knowledge and experience of family and friends.

Negative attitudes held by staff Shared understanding by all staff that family and friends are welcome and their attendance encouraged

Lack of acknowledgement of family members or friends, and the role they play

Respectful attitudes towards family and friends

Lack of visible resources Visible resources targeting family and friends

Lack of knowledge by staff of support or referral options for family and friends

Clearly articulated policies around issues of confidentiality

Lack of opportunities for feedback from family and friends regarding the experience of services

Community awareness and health promotion activities targeted towards family and friends

Opportunities for family and friends participation in service development and quality improvement activities

Barriers and enablers to creating engaging

and inclusive services

Training for all staff across headspace programs about the importance of family and friend inclusive practice and the ways to help facilitate and support their involvement is vital in creating a culture and environment which is engaging for family and friends. It also provides the support for headspace staff to overcome their fears and uncertainties in relation to working with family and friends so they can fully implement headspace policies and values.

While some clinicians may be sufficiently trained to provide formal family therapy, this level of training is not necessary in order to behave or practice in a family and friend inclusive way. Rather, training provided by centres and headspace National Office should be focused on the core skills needed to provide support to and engage family and friends in treatment, including:

Training and education can be delivered in a number of ways and incorporate innovative strategies, including face-to-face training sessions and workshops, webinars and other online formats, or via written manuals and guidelines. Training that incorporates the perspectives of those with an experience of supporting a young person with mental health difficulties is particularly beneficial and helps to ensure the appropriateness and credibility of the content.